The House of Wolfenbüttel-Brunswick and Its Enduring Regency Rights in the Netherlands

Table of Contents

-

Introduction

-

’s-Hertogenbosch: Name Rooted in Brunswick Heritage

-

Duke Louis of Brunswick: Regent of the Netherlands and Protector of Monarchs

-

Brunswick and the Making of Noord-Brabant

-

Napoleon, Vienna, and the Fate of Brabant

-

Brabantse Macht — Brabantian Power

-

Groot-Nederland and the Enduring Unity of the Low Countries

-

East Frisia: Northern Fringe of Groot-Nederland

-

From Cultural Geography to Constitutional Guardianship

-

Monuments and Memory of Brunswick in the Netherlands

-

The Brunswick Campaign Restoring the House of Orange in 1787

-

Regent-Family Correspondence and Dynastic Privileges

-

Dynastic Web: Brunswick, Mecklenburg, Orange, and the Russian Romanovs

-

Legal Continuity of the Romanov-Brunswick Claim

-

Regency Rights and Dutch Law

-

“Brunswick, Brabant, and the Flemish Question”

-

Conclusion: A Legacy Unfolding

Introduction

The House of Wolfenbüttel-Brunswick, a senior noble house of the Guelphs (Welfs), holds a uniquely pivotal position in European history. While often overshadowed in mainstream narratives by the Habsburgs and Hohenzollerns, the Brunswicks governed not only through direct territorial dominion but as de facto and de jure regents, protectors, and monarch-makers in several European states. Nowhere is this more evident than in their deep and constitutional legacy within the Netherlands, where the Dukes of Brunswick served as regents and guardians of the Dutch royal house during the nation’s formative stages.

’s-Hertogenbosch: Name Rooted in Brunswick Heritage

The city of ’s-Hertogenbosch (“The Duke’s Forest”) echoes the historical dominion of the Dukes of Brabant, a title often held or claimed by branches of the Brunswick line. These names preserve the memory of an era when the House of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel exercised territorial, military, and familial control in the region. The royal palace at The Hague, and the ducal associations of ’s-Hertogenbosch itself, stand as toponymic witnesses to a time when Brunswick and Orange were not distant cousins, but closely intertwined partners in rule.

Duke Louis of Brunswick: Regent of the Netherlands and Protector of Monarchs

Duke Louis Ernest of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (1718–1788) was not merely a passing adviser in Dutch history; he was the central regent figure who held together the Republic during a long and fragile transition. Trained in imperial service, he rose through the Habsburg ranks in the Turkish wars and the Second Silesian War, was wounded at Soor (1745), and fought again at Roucoux (1746) and Lauffeld (1747). By mid-century he had become both imperial Reichsgeneralfeldmarschall and, crucially, a Protestant general of the Holy Roman Empire’s forces, effectively the Protestant commander-in-chief within the imperial high command.

In 1750 he entered Dutch service as field marshal of the Republic; by 1751 he was Generalkapitän (General-Captain) of the United Provinces, and after the death of Princess Anna of Hanover in 1759 he became guardian and regent for the minor Prince William V of Orange. From 1751 to 1766 Louis Ernest governed as the effective head of government in the Netherlands, exercising wide patronage through local “mini-stadholders” and controlling appointments, promotions, and military reorganisation under the Orange name. For nearly fifteen years, Brunswick hands rested on the levers of Dutch power, shaping the constitutional Monarchy that emerged from the crisis-ridden Republic.

This regency did not occur in a vacuum. Louis Ernest stood at the crossing-point of three rival systems:

-

the Russian-Brunswick-Mecklenburg nexus, in which his brother Anton Ulrich married the Russian Grand Duchess Anna Leopoldovna of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, producing Tsar Ivan VI and briefly placing a Brunswick child on the Russian throne;

-

the Austrian camp, where Louis served as field marshal against his own Prussian-aligned kinsmen in the War of Austrian Succession;

-

and the Dutch regency, where he acted as protector, tutor, and effective co-ruler for three generations of Orange princes.

Even when his Russian and Courland adventure failed—he was elected Duke of Courland and Semigallia in 1741, then lost the title after the coup of Empress Elizabeth—Louis Ernest retained the imperial and Austrian confidence that later underpinned his Dutch authority. In practical terms, the “Wolfenbüttel army” and its officers became the backbone of order in Holland during an age of revolts, pamphlet wars, and foreign intrigue.

Brunswick and the Making of Noord-Brabant

Brunswick and the Border of Brabant

As Governor of ’s-Hertogenbosch and of the province of Noord-Brabant, Duke Louis Ernest did more than command troops. He presided over the consolidation of North Brabant as a loyal, integrated part of the Dutch state at precisely the moment when the southern Brabant lands were drifting toward what would become the Belgian revolutions. Contemporary Dutch museum material still describes him as “responsible for the administration of the province of Noord-Brabant,” which in practice meant navigating the delicate frontier between the Dutch Republic and the Austrian-ruled southern Netherlands and keeping the northern half stable and Orangist while the south slid into upheaval.

In that sense, one can fairly say that the House of Wolfenbüttel-Brunswick helped “draw and hold” the line between Noord-Brabant (within the Dutch constitutional orbit) and Zuid-Brabant (which would go on to form part of Belgium after the Brabantse Omwenteling of 1789–1790 and later revolutions). The long survival of the name “Brabant” in both countries owes something to this period of careful regency, in which Brunswick authority, Austrian claims and local Brabant identities had to be balanced without tearing the Low Countries completely apart.

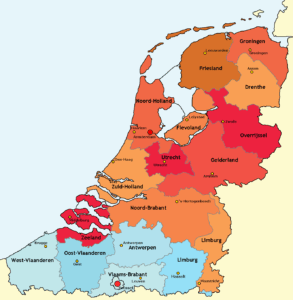

“Napoleon, Vienna, and the Fate of Brabant”

The Brabant frontier did not freeze in the 18th century. Under French revolutionary and Napoleonic rule, the Austrian Netherlands were annexed outright and reorganised into departments, including Dyle, centred on Brussels. This French territorial grid ignored many medieval lordships and dioceses but it proved enduring. When the Congress of Vienna created the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1815, the former French department of Dyle was simply rebaptised South Brabant, while the older northern strip, already under the Dutch Republic since the Eighty Years’ War, continued as Noord-Brabant. After the Belgian Revolution of 1830 and the Treaty of London (1839), these administrative lines hardened into the modern international border: North Brabant in the Kingdom of the Netherlands, and “Brabant” (later Flemish Brabant, Walloon Brabant, and Brussels-Capital) in Belgium.

From the perspective of dynastic right, this was yet another instance of might over right. The French departments and Vienna’s settlement were engineered without regard to historic, patrimonial titles in the region, and the House of Wolfenbüttel-Brunswick is one of the few princely houses that formally and repeatedly protested the Vienna-era reordering of North Germany and its annexations, through the annual protests of Duke Charles II and later Geneva proceedings. The Brabant frontier is thus not merely a neutral cartographic accident; it is part of the wider 19th-century struggle between dynastic law on one side and Napoleonic–Viennese power politics on the other.

At the same time, Louis Ernest’s broader allegiance network gives that border a distinctly imperial context. As an Austrian field marshal and Protestant Generalfeldzeugmeister of the Holy Roman Empire, he was one of the few princes who could speak credibly both to Vienna and to The Hague. As elected Duke of Courland, tied by blood to the Romanov–Mecklenburg-Schwerin line, and as guardian–regent of the House of Orange, he embodied three rival spheres at once: Russian, Austrian, and Dutch. Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Tourism In the end, his primary weight fell with the Netherlands, where he held direct command of the States Army and anchored the loyalty of Brabant to the Orange cause.

Brabantse Macht — Brabantian Power

🇳🇱 Dutch

Brabantse macht — de kracht van trouw en recht.

Terwijl wij uitzien naar de komende herdenking, gedenken wij de blijvende erfenis van het Huis van Wolfenbüttel-Brunswick en hun historisch regentschap in de Nederlanden — niet gebouwd op ambitie, maar op plicht, trouw en verbond.

“Ben ick van Duytschen Bloedt,

Den Vaderland ghetrouwe

Blijf ick tot inden doet.”

— Wilhelmus van Nassouwe

Moge de komende herdenking ons opnieuw verbinden met deze eeuwenoude waarden:

geloof, gerechtigheid, en de eenheid van ons volk.

Brabantse macht — tot eer van geschiedenis en toekomst. 🕊️

🇺🇸 English Translation

Brabantian Power — the strength of loyalty and law.

As we look forward to the next commemoration, we remember the enduring legacy of the House of Wolfenbüttel-Brunswick and its historic regency in the Netherlands — built not on ambition, but on duty, fidelity, and covenant.

“I am of Germanic blood,

Faithful to my homeland

I shall remain until my death.”

— The Dutch National Anthem, Wilhelmus

May the coming remembrance reconnect us to these ancient principles:

faith, justice, and the unity of our people.

Brabantian Power — honouring both history and the future. 🕊️

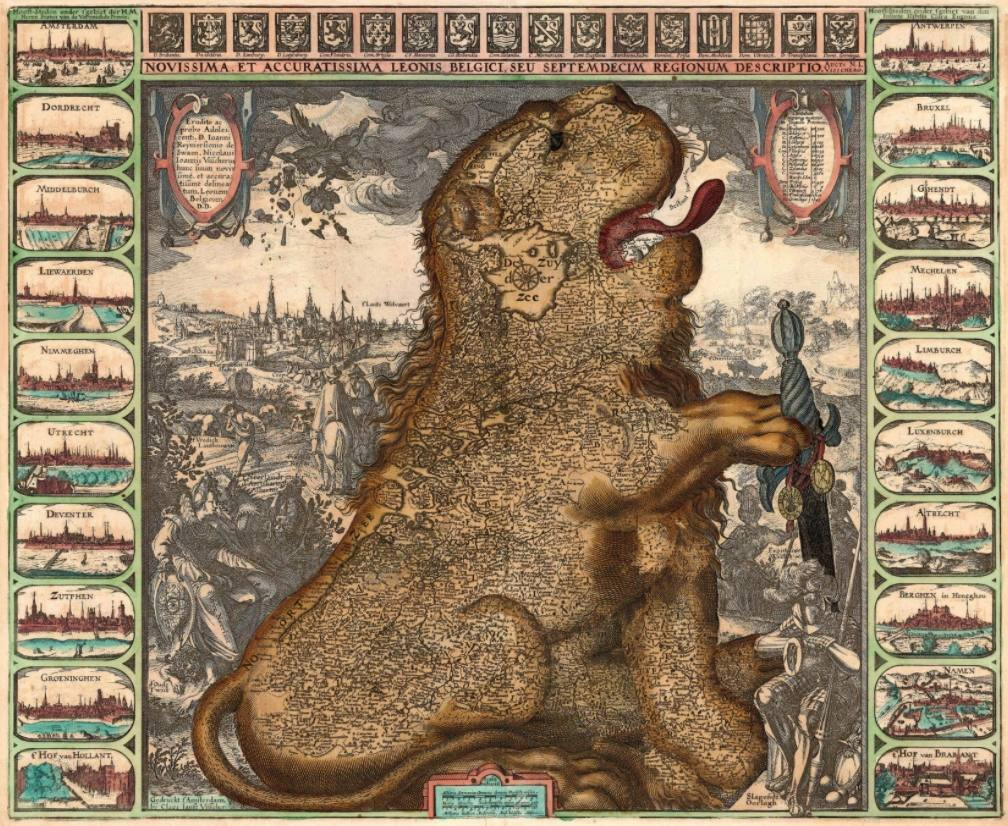

Groot-Nederland

Groot-Nederland and the Enduring Unity of the Low Countries

The historical role of the House of Wolfenbüttel-Brunswick in stabilizing Brabant also resonates with the deeper cultural idea known as Groot-Nederland—the vision of a shared civilizational and linguistic heritage uniting the Dutch and Flemish peoples across present borders. Long before modern political divisions, Brabant, Flanders, Holland, Zeeland and Gelderland formed a coherent cultural and economic world, and the House of Orange-Nassau and the House of Brunswick repeatedly acted as guardians of this broader Low Country unity. Many in Flanders today continue to feel a closer kinship with the Netherlands than with the francophone Belgian state created in 1830, and the modern Flemish national movement still recalls the older Dutch-Germanic identity expressed in the Wilhelmus and in the pre-Napoleonic territorial order. In this light, the Brunswick regency and the defense of Brabant against revolutionary fragmentation appear not merely as a military intervention but as a defense of a single historic people, protecting the continuity of a shared nationhood rooted in loyalty, language, law and Christian heritage. The preservation of Noord-Brabant within the Dutch sphere—rather than its absorption into French-controlled Belgium—remains a cornerstone of this older idea of unity: one Low Country, many provinces, but one cultural heart.

Groot Nederland

East Frisia: Northern Fringe of Groot-Nederland:

If one extends the Groot-Nederland horizon beyond today’s political borders and looks instead at the historic Low Countries world, then East Frisia (Ostfriesland) naturally belongs in the discussion. For centuries this coastal strip was oriented more toward the North Sea and the Dutch provinces than toward inland Germany. Medieval “Frisian Freedom,” Dutch-speaking trading cities like Emden, and close political, economic, and religious ties with the Dutch Republic all meant that East Frisia developed alongside the Low Countries rather than the German interior. Historians of East Frisia explicitly note that from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries Netherlandish influence was decisive—politically, economically and culturally.

Constitutionally, East Frisia also passed through the same Napoleonic and post-Napoleonic crucible that reshaped the Netherlands and Belgium. After the extinction of the Cirksena counts, Prussia took over East Frisia in 1744 under the Emden Convention. During the Napoleonic era the region was first attached to the Kingdom of Holland (1807) and then annexed directly to France (1810), before being restored to Prussia in 1813. At the Congress of Vienna (1815) East Frisia was transferred to the Kingdom of Hanover, whose ruler was simultaneously King of Great Britain and (by title) Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg. In 1814 Hanover even bartered Saxe-Lauenburg against Prussian East Frisia, underlining its value as part of the wider Welf–Brunswick inheritance sphere. Only in 1866, after the Austro-Prussian War and the annexation of Hanover, was East Frisia finally folded back into Prussia as part of the Province of Hanover, where it remained into the First World War.

From a dynastic-Brunswick point of view, this history is not accidental. The Hanoverian crown that administered East Frisia in the nineteenth century rested on the same Brunswick-Lüneburg patrimony whose senior Wolfenbüttel branch is represented by Duke Charles II and his successors. Within that internal house-law logic—articulated in instruments such as the 1827 Edict, the 1770 property law and later Geneva proceedings—East Frisia lies within the circle of Germanic coastal territories whose rightful succession is argued to have devolved, after the extinction or forfeiture of other lines, upon the Wolfenbüttel house rather than upon Prussia’s de facto annexations. In this sense, East Frisia enlarges not only the historic map of Groot-Nederland (as a Dutch-Frisian maritime culture zone), but also the moral map of “Right over Might”: a coastal province whose people and history look seaward to the Low Countries, yet whose political fate was repeatedly dictated by Prussian power politics.

For present purposes, it is enough to say that any honest map of the old Netherlands world must shade in East Frisia alongside Brabant, Flanders and Holland: a North Sea fringe where Frisian, Dutch and German identities meet, and where the Brunswick–Welf inheritance and the Groot-Nederland idea quietly overlap.

From Cultural Geography to Constitutional Guardianship

What the Groot-Nederland horizon reveals geographically, the Brunswick regency demonstrates politically: the House of Wolfenbüttel-Brunswick did not merely inherit territories and alliances, but actively shaped and defended the constitutional structure and stability of the Dutch state.

In historical terms as well as in sentiment, the legacy of Brunswick stewardship in Brabant was not symbolic but structural, shaping the very borderlines and constitutional continuity of the modern Dutch state.

For this accomplishment, Brunswick deserves historic recognition as one of the principal architects of the modern Dutch frontier. Without his balancing of Austrian, Dutch, and regional Brabant interests, the territorial identity of Noord-Brabant might well have fractured or been absorbed into the southern revolutions. Instead, under Brunswick stewardship, it remained firmly within the Dutch sphere and preserved the constitutional continuity of the northern provinces. This is one of the clearest examples of why the Netherlands owes a debt of gratitude to the House of Brunswick, and why commemorations of his regency remain fitting and historically justified today.

The 1787 Capitulation of Amsterdam medal is therefore more than a commemorative token—it is a material witness to the decisive Brunswick role in preserving Dutch constitutional order. Struck in the immediate aftermath of the city’s peaceful submission, the medal publicly credited Karel Willem Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick, as the commanding general whose leadership restored Amsterdam to stability under the House of Orange. Its imagery—Amsterdam subdued without bloodshed, flanked by the heraldic shields of the Seven Provinces—proclaims the moment when the Dutch Republic was rescued from fragmentation and civil war. The circulation of this medal across the Netherlands was itself a civic endorsement that Brunswick authority had acted not as a conqueror, but as a protector, re-establishing legal governance without imposing foreign rule. In that light, the medal stands both as a historic artifact and as a reminder of the profound debt of national gratitude owed to the House of Brunswick.

Monuments and Memory of Brunswick in the Netherlands

The Dutch landscape still bears quiet witness to this Brunswick debt of gratitude.

-

In ’s-Hertogenbosch, the former Gouvernementshuis in Verwersstraat 41 – purpose-built in the 1760s as the residence of the military governor – was renewed under Lodewijk Ernst, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, and served as his palace until 1784. The building is now a listed monument and houses the Noordbrabants Museum, where Louis Ernest’s role as governor of Noord-Brabant is explicitly highlighted.

-

Inside the Noordbrabants Museum, you find a formal portrait of Lodewijk Ernst by Jacobus Vrijmoet and a city view of ’s-Hertogenbosch surmounted by his coat of arms – visual reminders that the city and province were once under Brunswick governance. Haags Gemeentearchief

-

In ’s-Hertogenbosch civic life, the city fathers marked 25 years of his governorship with a special vroedschapspenning (council medal) engraved by Theodorus Victor van Berckel, celebrating “Lodewijk Willem Ernst, hertog van Brunswijk-Wolfenbuttel, sinds 25 jaar gouverneur van ’s-Hertogenbosch.” Medals like this function as portable monuments to the Brunswick regency.

-

In The Hague and Amsterdam, Brunswick appears in the allegorical monumental imagery of the period. A famous print in the Rijksmuseum shows a triumphal arch and monument “in honour of the King of Prussia for the restoration of the stadtholdership of William V” – with the King of Prussia and the Duke of Brunswick explicitly depicted as the “liberators of the United Netherlands.” This kind of printed “monument” mirrors the temporary arches and illuminated structures actually erected in Dutch cities to honour the Prussian–Brunswick intervention of 1787.

-

In The Hague’s built environment, Brunswick’s presence endured even in place-names: a residence known historically as the Hotel van Brunswijk recalled his status at court long after his fall from favour.

Taken together, these palaces, portraits, medals, triumphal-arch images and place-names amount to a scattered monument-system to the House of Brunswick. They testify that, whatever later Patriot propaganda said about the “Dikke Hertog,” the Dutch establishment repeatedly marked and memorialised Brunswick as a guardian of order, particularly in Brabant and in the restoration of the House of Orange.

The Brunswick Campaign Restoring the House of Orange in 1787

This protective role re-emerged in decisive military form in 1787, when Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel—Louis Ernest’s nephew and a Prussian field-marshal—led the intervention that saved the Dutch monarchy from effective overthrow by the Patriot movement. Following the unlawful detention of Princess Wilhelmina of Prussia, consort of Stadholder William V, King Frederick William II of Prussia entrusted Brunswick with an expeditionary army of roughly 20,000–26,000 troops with a clear mandate: disarm the Patriots and restore the Stadholder’s powers.

The Brunswick-led forces crossed the border in September 1787 and, in a rapid, almost bloodless campaign, occupied Nijmegen, forced the evacuation of Utrecht, compelled the surrender of fortified cities such as Gorinchem and Dordrecht after brief bombardment, entered The Hague amidst Orangist celebrations, and finally broke the outer defences of Amsterdam. Constitutional historians agree that this operation re-imposed the ancient Dutch constitution and restored the House of Orange to sovereign command. Far from being a foreign invasion in the modern sense, the intervention functioned as a hereditary Regent-Protector house marching in to secure its ward’s lawful throne.

In this way, the Brunswicks’ regency in the Netherlands was both internal and external: first through the constitutional guardianship and secret consultative authority of Louis Ernest, and later by the open, armed restoration of Orange rule under Charles William Ferdinand. Together, these episodes form a continuous Brunswick protectorate over the Netherlands.

This gratitude was not merely recorded in state documents or diplomatic correspondence; it was engraved into Dutch civic memory.

A vivid material testimony to Dutch gratitude toward the House of Brunswick is preserved in the historic 1787 commemorative medal titled “Capitulatie van Amsterdam, ter ere van Karel Willem Ferdinand, Hertog van Brunswijk.” Struck following the peaceful surrender of Amsterdam in October 1787, the medal features the Duke’s bust on the obverse, and on the reverse a panoramic view of Amsterdam—flanked above and below by the aligned shields of the Seven Provinces, crowned and united. This civic medal was not a partisan keepsake, but a public monument in metal: a national expression that Brunswick restored constitutional government and brokered peace, ending bloodshed and division. Issued by Dutch civil authorities and widely circulated, it stands today in museum collections from Amsterdam to Berlin, confirming that the Netherlands itself recognized Brunswick’s decisive role and publicly honored the Duke as the restorer of liberty and national stability. The existence of such a medal reinforces the broader historical reality that Dutch national identity—territorial unity, constitutional continuity, and the political boundary of the northern provinces—was secured through Brunswick intervention and statesmanship.

The 1787 Capitulation of Amsterdam medal is therefore more than a commemorative token—it is a material witness to the decisive Brunswick role in preserving Dutch constitutional order. Struck in the immediate aftermath of the city’s peaceful submission, the medal publicly credited Karel Willem Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick, as the commanding general whose leadership restored Amsterdam to stability under the House of Orange. Its imagery—Amsterdam subdued without bloodshed, flanked by the heraldic shields of the Seven Provinces—proclaims the moment when the Dutch Republic was rescued from fragmentation and civil war. The circulation of this medal across the Netherlands was itself a civic endorsement that Brunswick authority had acted not as a conqueror, but as a protector, re-establishing legal governance without imposing foreign rule. In that light, the medal is both a historic artifact and a reminder of the profound debt of national gratitude owed to the House of Brunswick.

Regent-Family Correspondence and Dynastic Privileges

The regent status of the House of Brunswick also finds grounding in the established Dutch tradition of elite regent-family privileges, reflected especially in the historic contracten van correspondentie—formal agreements among ruling houses to reserve high offices and prerogatives for their scions (nazaten). These arrangements secured privileged access to governance, appointments, and direct channels of correspondence and influence with the Stadholder and the court.

Within this framework, the House of Wolfenbüttel-Brunswick did not stand apart as a mere foreign princely house, but as a recognised regent dynasty, whose descendants possessed enduring ceremonial and correspondence privileges. Their status as hereditary protectors, combined with marital ties and constitutional service, placed Brunswick among those families whose lineal heirs were understood to enjoy a special right of direct approach and communication with the House of Orange.

Dynastic Web: Brunswick, Mecklenburg, Orange, and the Russian Romanovs

The House of Brunswick was interwoven not only with the Dutch royal house, but also with imperial Russia and the House of Mecklenburg, which itself was drawn into the wider Orange orbit. Through Empress Charlotte of Wolfenbüttel, the Brunswicks married into the Romanov dynasty. Her descendants included Emperor Peter II and later Emperor Ivan VI Romanov-Brunswick, the rightful Tsar of Russia under Peter the Great’s 1722 succession decree. At the same time that the House of Mecklenburg was connected into the Orange line and recognised among the kin of the Dutch monarchy, the Brunswick family ascended the Russian throne through Ivan VI, binding these three houses—Brunswick, Mecklenburg, and Orange—into a tightly knit dynastic triangle.

Ivan VI, born to Duke Anthony Ulrich of Brunswick and Grand Duchess Anna Leopoldovna of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, was lawfully appointed Tsar under imperial succession law. His uncle, Duke Louis of Brunswick, served simultaneously as Duke of Courland, suitor to Empress Elizabeth, and military commander in both Austria and the Netherlands. During this period, the Brunswick and Orange houses did not drift apart; rather, their relationship deepened, as the same Brunswick and Mecklenburg kinship network served the interests of both courts.

Even after Ivan’s violent usurpation and eventual murder under Catherine the Great, these family ties endured. The Christening of Duke Charles II von Wolfenbüttel-Brunswick later became a highly symbolic moment: attended by the Emperor of Russia, the Mecklenburg family, and representatives of the Dutch royal house, it signalled the recognition of Charles II as a scion heir-at-law of these three interconnected dynasties. In him, the legacies of Brunswick, Mecklenburg, and Orange-Romanov converged in one person, reaffirming the Brunswick role as a natural mediator and regent-house between these realms.

Legal Continuity of the Romanov-Brunswick Claim

The Brunswick claim to the Russian throne remained legally valid:

-

The 1722 law permitted the reigning monarch to name a successor, which Empress Anna did in naming Ivan VI von Wolfenbuttel-Brunswick.

-

The Pauline Laws of 1797 did not retroactively invalidate the prior succession.

-

The House of Brunswick never renounced its claim to the Russian throne; under international law, such a claim endures until formally relinquished.

-

A 1935 Geneva court case recognized Ulric de Guelph Civry Brunswick as successor, maintaining the estates and titles in legal custodianship and keeping the Brunswick-Romanov rights alive in a juridical sense.

Thus, while violently suppressed, the Romanov-Brunswick succession and its associated estates have never been extinguished in law.

Regency Rights and Dutch Law

To this day, successors of the House of Wolfenbüttel-Brunswick maintain correspondence rights with the Dutch royal family under historical regency customs. These are not mere formalities but rest on:

-

Proven regent status over multiple generations in the Netherlands.

-

Familial marriage ties and direct service in Holland, including military and constitutional guardianship of the House of Orange.

-

International and constitutional principles safeguarding the rights of royal protectors and peers, whose historic regency roles are acknowledged even when their territorial rule is in abeyance.

It is thus lawful and appropriate that when a descendant of this line returns to the Netherlands, the state honours the traditional right of residence, hospitality, and regency acknowledgment that has long been accorded to the House of Wolfenbüttel-Brunswick.

“Brunswick, Brabant, and the Flemish Question”

The Brabant strip between the Meuse and Scheldt remains today a zone where questions of identity and allegiance are unusually intense. Historically, the Brabant Revolution of 1789–1790 in the Austrian Netherlands rallied Catholic estates under the name of Brabant to overthrow Habsburg centralisation and create the United Belgian States. Under French and Napoleonic rule, the same ground became the battlefield of Europe, culminating in Waterloo just south of the present Dutch border. After 1815, North and South Brabant were briefly reunited in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, only to be separated again by the Belgian secession.

In modern times, the Flemish Movement and Groot-Nederland thinkers have argued that the Dutch and Flemish form one Netherlandic or “Diets” people, whose unity was broken by foreign dynastic settlements and religious politics rather than by any natural ethnic or linguistic division. Many Flemings in Brabant and Flanders feel culturally closer to the Netherlands than to a Francophone, Jacobin conception of Belgium, and view the Belgian state as an extension of French influence. In that light, the old Brunswick regency over the Low Countries — Dutch, Germanic, and cross-border by nature — offers a different memory: not of Parisian centralism, but of a Germanic protector-house maintaining constitutional order in both Holland and Brabant. Commemorating Brunswick’s role in Brabant therefore speaks not only to Dutch history, but also to Flemish readers who still sense that Brabant belongs to a wider Netherlandic and Germanic commonwealth.

Conclusion: A Legacy Unfolding

In light of this, any commemoration at ’s-Hertogenbosch or in Noord-Brabant is not nostalgia, but a measured acknowledgment that the House of Wolfenbüttel-Brunswick helped hold the Dutch south together, negotiated its balance between Holland and the Burgundian Low Countries, and left behind the borders from which the modern Netherlands still profits.

The House of Wolfenbüttel-Brunswick stands as a senior stem duchy of Europe with legitimate, uninterrupted claims to nobility, sovereignty, and dynastic leadership. Whether in Russia, Germany, or the Netherlands, their influence transcends time. The acknowledgment of their regency rights in the Netherlands remains not only a matter of historical record but of ongoing legal and dynastic relevance.

In the spirit of historical continuity and justice, these claims and their recognition form a cornerstone for any future reconciliation of European nobility under law and tradition.

This article is to be published under the Sovereignty and Nobility section of the House of Wolfenbüttel-Brunswick within the Institute’s historical legal research initiative.